SAFe or Scaled Agile Framework

What is SAFe?

Many people are familiar with the concept of Agile. Even more people involved in IT use the terminology. And even more have heard about Agile.

However, not everyone who confidently uses the term "Agile" for communication, critique, or to present their team or company in a better light understands, for example, the difference between SCRUM and Agile. Often, they equate these two distinct concepts. But in 2015, a new term emerged—SAFe. What is it, and why is it necessary?

One of the key advantages and disadvantages of SCRUM, in my opinion, is the prescribed team size—7±2 (or 3-9 according to the latest Scrum Guide), including the Product Owner. Certainly, 9 highly skilled and well-motivated professionals are capable of achieving a lot, but sometimes, there is a need to build something that requires more hands, heads, eyes, and brains, in the end. Expanding teams is a bad idea, which means that the number of teams must increase. However, this introduces the problem of communication between teams, synchronization of work, and SCRUM itself does not offer a solution for these issues. There have been attempts to manage SCRUM at the level of SCRUM teams (as recommended by Jeff Sutherland, one of the authors of the Agile Manifesto), there’s Large Scale Scrum, Disciplined Agile Delivery, and many other methods, but there is also SAFe—Scaled Agile Framework.

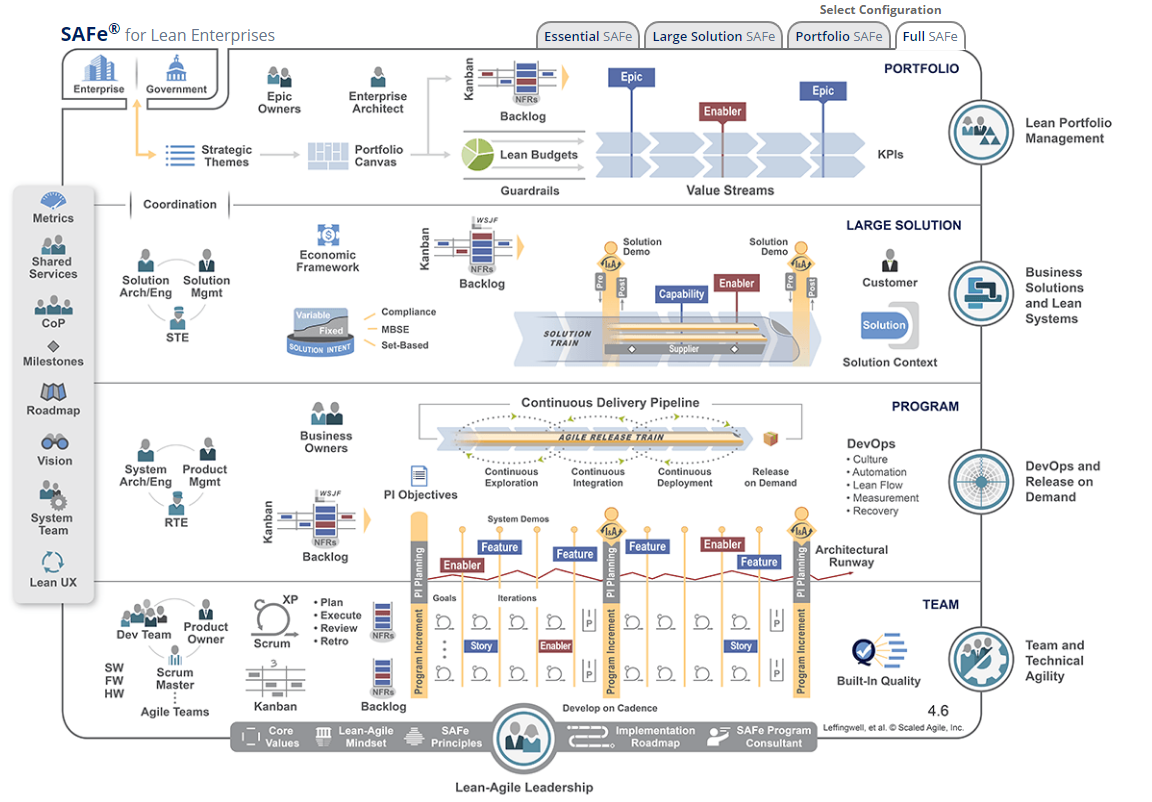

SAFe is a framework for managing a company where coordination is required for work on a project or related projects involving 5 or more SCRUM teams. It acts as a layer on top of SCRUM, enabling the management of groups consisting of 100 or more people.

The benefit?

First and foremost, this methodology is, of course, beneficial to those who sell it and offer training on it. Dave Thomas (another author of the Agile Manifesto) commented on this topic quite well during his presentation Agile is Dead at GOTO 2015.

Secondly, program management departments. Those who used to manage projects, obtain PMP certifications, create Gantt charts, and implement the concept of firm-soft management (soft towards leadership and firm towards executors) now find a role in SAFe. The issue is that in typical SCRUM, there is no function for them, but in SAFe—there is. The same applies to various types of architects. In SCRUM, there is no function for them, but SAFe provides a clear career path.

Next, it could be beneficial to business owners whose managers work on large projects that consume an enormous amount of man-hours and who cannot (sometimes for objective reasons) make these projects independent.

Also, for a large number of developers with below-average qualifications, since often, exponentially more of them are needed to accomplish something compared to those same experienced and motivated professionals.

In general, it benefits the industry. Since the number of developers doubles every 5 years (see Uncle Bob's Future of Programming), the consequence is that at any given time, at least half of the developers have less than 5 years of experience. If this trend doesn’t change, and it seems it won’t, processes are required to prescribe and formalize their work functions, mechanisms of interaction between participants, and overall processes.

SAFe is like a multi-layered cake of various Agile methodologies. At the bottom level is a nearly traditional SCRUM with typical two- to three-week sprints and teams of 3-9 people, including the Product Owner. All the standard rituals are in place, from the daily standups to the retrospective meetings. However, there is one key difference: the team ceases to be a fully functional, independent unit, and the sprint is no longer an independent time block with a complete lifecycle. Sprints are grouped into Program Increments (PIs), usually consisting of five sprints. So, if in classical SCRUM we build something the client doesn’t like, we can correct the course in the next sprint. But in SAFe, we continue heading toward the cliff until the end of the Program Increment, potentially up to the next four sprints (of course, I’m exaggerating a bit).

At the next level, we have the trains—the so-called Agile Release Train (ART). To manage these five-sprint segments, new roles emerge—System Architect (who owns the architecture, meaning the team no longer does), Product Manager (who manages the product, and not the Product Owner, who now seeks advice from the Product Manager), and RTE (Release Train Engineer, essentially the PMP from the waterfall world). Some Kanban practices are applied here, like boards, prioritization methods, and the principle of measuring historical team performance (velocity). Projections of what will be built by the end of the time block are made, as opposed to setting deadlines for fixed functionality (scope). One innovation is that the final sprint of the five is declared an organizational sprint. During this sprint, massive meetings are held (with all teams—100+ people), technical debt is analyzed, plans for architecture work are developed, and all teams synchronize their work.

Above the train level is the coordination between departments, directors, and the client. This level borrows heavily from Lean Agile while retaining Kanban tools. Here, an analysis of the economic feasibility of changes takes place. Ideally, any change undergoes a preliminary analysis, where a measurable hypothesis about the upcoming change is proposed (for example, "if we move the online store from a data center to the cloud, we will be able to increase the number of transactions by 10% during peak seasonal sales by rapidly scaling capacity"). This hypothesis is then either confirmed or rejected. For companies with less than a billion dollars in revenue, this might be the highest layer. This level also involves planning work for the next 12-36 months (hello to five-year plans for quality, quantity, etc.).

Above the large systems level is portfolio management. Here, funds are allocated to various business areas using Lean Portfolio Management. Based on the company’s development strategy, directions are chosen that offer potential returns. Decisions are made about acquisitions or mergers with other companies, creating new business areas, or shutting down old ones. Budgets are regularly adjusted and reallocated (in contrast to quarterly or annual plans). For each portfolio component, a set of more or less standardized metrics is defined, and everything is evaluated based on them. As with the previous three levels, there are special synchronization rituals every two weeks (usually), where status updates and key indicators are exchanged.

At the very top is the strategy. However, the framework does not describe how this strategy is determined.

Advantages:

- A significant number of quite useful tools (WSJF, Kanban, Gemba, etc.).

- Steps for the SDLC (Software Development Life Cycle) are formalized and prescribed, starting from writing code (TDD is recommended) to static scanning, CI/CD, and feature toggles. Whether each practice is good or not is another question, but at least there is a plan, and everyone follows it.

- The process is understandable, explainable, and implementable.

- Every person in this process is assigned a well-defined role.

- The company becomes more transparent for those who work in it.

Disadvantages:

- It takes a relatively long time to respond when expectations do not match reality.

- A huge amount of resources and money is spent on communication and meetings.

- Often, the recommended solutions within the framework are outdated.

Should it be implemented?

In my opinion, if there’s a choice—no, it’s better to reduce dependencies between departments and projects. But if there’s no choice and you need to manage a massive project, then it’s definitely a viable option.

this is translation of my article written in 2018